A floating point number is normalized when we force the integer part of its mantissa to be exactly 1 and allow its fraction part to be whatever we like.

For example, if we were to take the number 13.25, which is 1101.01 in binary, 1101 would be the integer part and 01 would be the fraction part.

I could represent 13.25 as 1101.01*(2^0), but this isn’t normalized because the integer part is not 1. However, we are allowed to shift the mantissa to the right one digit if we increase the exponent by 1:

1101.01*(2^0) = 110.101*(2^1) = 11.0101*(2^2) = 1.10101*(2^3)

This representation 1.10101*(2^3) is the normalized form of 13.25.

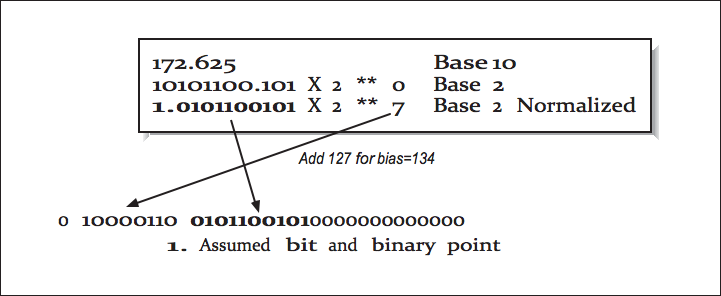

That said, we know that normalized floating point numbers will always come in the form 1.fffffff * (2^exp)

For efficiency’s sake, we don’t bother storing the 1 integer part in the binary representation itself, we just pretend it’s there. So if we were to give your custom-made float type 5 bits for the mantissa, we would know the bits 10100 would actually stand for 1.10100.

Here is an example with the standard 23-bit mantissa:

As for the exponent bias, let’s take a look at the standard 32-bit float format, which is broken into 3 parts: 1 sign bit, 8 exponent bits, and 23 mantissa bits:

s eeeeeeee mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm

The exponents 00000000 and 11111111 have special purposes (like representing Inf and NaN), so with 8 exponent bits, we could represent 254 different exponents, say 2^1 to 2^254, for example. But what if we want to represent 2^-3? How do we get negative exponents?

The format fixes this problem by automatically subtracting 127 from the exponent. Therefore:

0000 0001would be1 -127 = -1260010 1101would be45 -127 = -820111 1111would be127-127 = 01001 0010would be136-127 = 9

This changes the exponent range from 2^1 ... 2^254 to 2^-126 ... 2^+127 so we can represent negative exponents.